Dear Friends,

This past week my wife Ellen and I participated in the Living Legacy Pilgrimage, a civil rights pilgrimage tour. Our dear friend Reggie Harris was one of the leaders of the trip. It was an intensive journey, as we visited key sites, memorials and museums throughout Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee, while meeting with veterans of the civil rights movement and with the adult children of some of the martyrs of that era. The trip was organized by the Living Legacy Project of the Unitarian Universalist Association.

This was truly a pilgrimage as we literally retraced the footsteps of many key civil rights activists, those known to history, and those unsung. In Montgomery, Alabama, the capital of the Confederacy and a center of institutionalized racism, we stood at the site of the bus stop where, on December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing a bus driver’s instructions to give up her seat to a white passenger. Her bravery initiated the Montgomery bus boycott, the first successful non-violent resistance to Jim Crow segregation. Parks later recalled that her refusal wasn’t because she was physically tired, but that she was tired of giving in. That bus stop stands directly across the street from the Legacy Museum, built on the site of a former warehouse where black people were enslaved. The museum traces the evolution of slavery into contemporary institutionalized forms of racism, in particular the continuing mass incarceration of millions of African Americans in our country today.

We walked a few blocks up to the Dexter Avenue church, where their new pastor, a young man named Martin Luther King, Jr., was enlisted to lead the boycott, which was organized in that church’s basement. That church stands across from the Alabama State Capitol, and also across from the house that served as the Confederate “White House,” Jefferson Davis’s home during the Civil War.

From there we passed by the Greyhound bus station, now a museum, where in 1961 the Freedom Riders, testing a Supreme Court decision banning segregation on interstate buses, risked their lives traveling those buses throughout the South. A short distance from there we visited the unspeakably powerful National Memorial for Peace and Justice, known as the Lynching Memorial. The memorial is the brainchild of Bryan Stevenson, a public interest lawyer who has worked for decades to change the narrative about race in America. In the era of Jim Crow, many thousands of African Americans were lynched, often as public spectacle. It was state-sponsored terrorism, and no one was ever punished for these crimes. Inspired by the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin, Stevenson wanted to create a similar public memorial for the black victims of lynching terror, so that these forgotten individuals could finally be honored and remembered, and so that the reality of racism and its victims could no longer be diminished or dispelled.

And this was only a few hours of a week-long tour. My experience was exhausting and overwhelming, but I knew I wanted to walk in these places, and to hear these stories. As a Jew, I have felt compelled to walk in the footsteps of my ancestors in Israel and in Europe marking both the uplifting and the tragic and horrific episodes of Jewish history, bearing witness with my presence that these memories will live on and continue to inspire. As an American, I feel compelled to walk in the footsteps of African American heroes (and “she-roes!”), the countless brave folks who, along with their white allies, risked their bodies and lives so that the promise of America could come closer to fulfillment. I want to honor their historic efforts, and keep that dream alive.

And so we journeyed: to Marion, Alabama to visit the grave of Jimmie Lee Jackson, whose murder on February 26, 1965 by a white mob sparked the historic march from Selma to Montgomery. To Selma, where a young John Lewis (now Congressman John Lewis) led a march across the Edmund Pettis bridge. The white police officers beat these marchers with such a fury – Lewis’ skull was fractured – that images of the attack shocked the national consciousness. The march that proceeded to the steps of the Capitol in Montgomery led directly to the passage by Congress of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which finally gave African Americans the unequivocal right to vote, one full century after they had been emancipated from slavery. Our group walked silently over the Edmund Pettis bridge.

In Selma we also spent time with Joanne Bland. Joanne was ten years old the first time she was arrested, for standing with her grandmother in front of the Selma courthouse as her grandmother waited to register to vote. Over the next two years Joanne would be arrested ten more times. Joanne continues her activism to this day. Joanne was just one of thousands of African American children who joined the struggle, facing firehoses and attack dogs and repeated arrests. Images of those children on television and in newspapers throughout the nation were a key factor in the dismantling of segregation.

We journeyed to Neshoba County, Mississippi, and stood by the grave of James Chaney. His gravestone is bolstered by steel girders to prevent it being toppled by vandals, which has happened many times in the past. On June 21, 1964 21-year-old Chaney was murdered along with Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, two young Jewish men from New York who were participating in Freedom Summer organizing activities in Neshoba County. At Chaney’s grave we met his daughter Angela, a radiant being who spoke with us about the healing power of love. Angela never met her father; her mother was pregnant with her when James was murdered. Angela told us about her painful yet healing journey, and brought us all to tears.

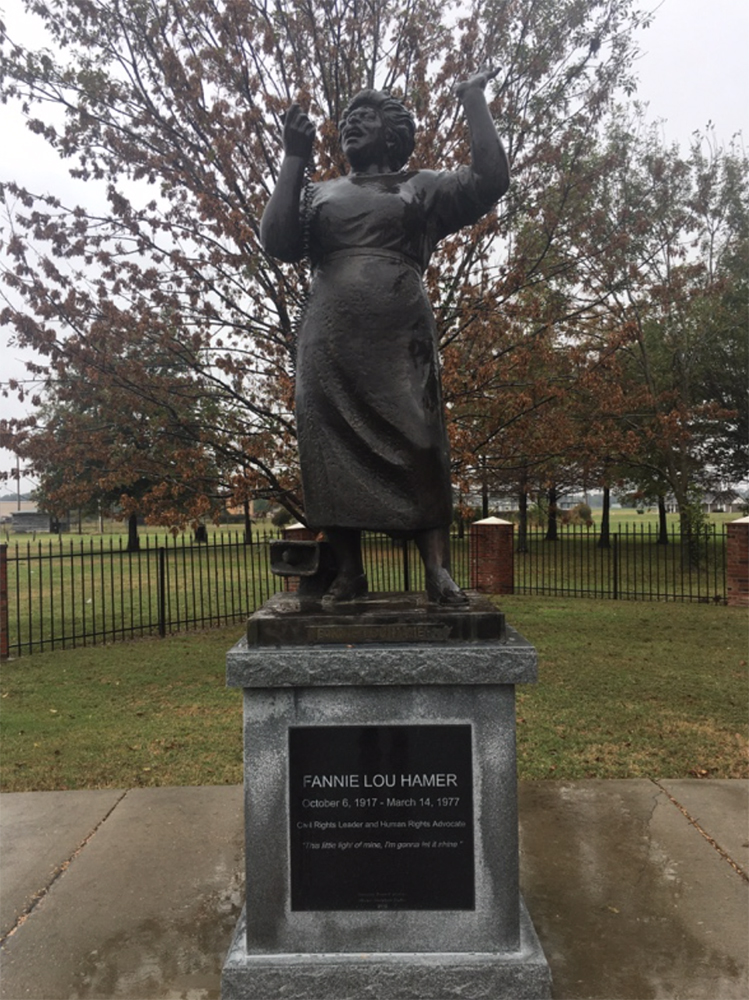

We stood in front of the ruined store in Money, Mississippi where 14-year-old Emmett Till of Chicago, visiting his relatives for the summer, was accused of whistling at a white woman, and was subsequently tortured and murdered by the woman’s family. In Ruleville, Mississippi we stood at a beautiful memorial to Fannie Lou Hamer, a sharecropper who was fired from her backbreaking field job when she attempted to register to vote. Fannie Lou Hamer then traveled to the 1964 Democratic Convention in Atlantic City where she electrified the nation as she testified as to why the unrecognized Mississippi Freedom Party should be seated at the convention in the place of the official all-white Mississippi delegation.

We stood in front of the ruined store in Money, Mississippi where 14-year-old Emmett Till of Chicago, visiting his relatives for the summer, was accused of whistling at a white woman, and was subsequently tortured and murdered by the woman’s family. In Ruleville, Mississippi we stood at a beautiful memorial to Fannie Lou Hamer, a sharecropper who was fired from her backbreaking field job when she attempted to register to vote. Fannie Lou Hamer then traveled to the 1964 Democratic Convention in Atlantic City where she electrified the nation as she testified as to why the unrecognized Mississippi Freedom Party should be seated at the convention in the place of the official all-white Mississippi delegation.

In Jackson, Mississippi we stood at the home of Medgar Evers, where on June 12, 1963 he was assassinated by a member of the White Citizen’s Council, as his wife and three children cowered inside their home. Evers was the Mississippi Field Secretary for the NAACP. He endured countless death threats as the public voice for equal rights in Mississippi. Where did he get his courage? His widow Myrlie Evers-Williams, an activist in her own right, became chairwoman of the NAACP in 1995. At Barack Obama’s second inaugural ceremony in 2012, Evers-Williams delivered the invocation.

Finally, we drove up to Memphis, Tennessee. We visited the National Civil Rights Museum, which is housed in and around the former Lorraine Motel. In April 1968 the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. stayed at the Lorraine Motel when he came to Memphis to support the black sanitation workers who were trying to unionize, a struggle that was ultimately successful. It was here in Memphis that Dr. King gave his last speech, the night before he was assassinated. The museum leads the visitor from the beginnings of the slave trade through the entire centuries long struggle for African Americans to be treated like full human beings in our nation. This is obviously a struggle that has not ended, as we continue to have to fight for the simple, most basic recognition that black lives matter.

Finally, we drove up to Memphis, Tennessee. We visited the National Civil Rights Museum, which is housed in and around the former Lorraine Motel. In April 1968 the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. stayed at the Lorraine Motel when he came to Memphis to support the black sanitation workers who were trying to unionize, a struggle that was ultimately successful. It was here in Memphis that Dr. King gave his last speech, the night before he was assassinated. The museum leads the visitor from the beginnings of the slave trade through the entire centuries long struggle for African Americans to be treated like full human beings in our nation. This is obviously a struggle that has not ended, as we continue to have to fight for the simple, most basic recognition that black lives matter.

The museum takes the visitor through African American history, from the establishment of the slave trade through the Civil War, from the heady period of post-war Reconstruction through the steady and brutal disenfranchisement of African Americans that became known as Jim Crow, and then through the ever-burgeoning, deadly, and inspiring struggle for civil rights. And then the museum leads you to the balcony and room of the Lorraine Motel where King was staying, and you stand inches away from where, on April 4, 1968, the assassin’s bullet felled Martin Luther King. Not for the first time on this pilgrimage, I wept.

Though it may be hard to believe, I am only describing a modest portion of the experiences, places and speakers that made up our tour. I hope this brief report will motivate all of us to refresh our memories and understanding of the import of the African American struggle for freedom and equal rights upon our nation and upon the world. And even though Dr. King’s career and assassination make for a dramatic narrative arc in telling the story, the struggle, of course, continues. I am heartened that in the decades since King’s death, despite the dogged entrenchment and at times resurgence of racism in the American South, the African American narrative is now visible and being told in museums and memorials all over the region. I think it is our duty as Americans to know and to teach this history, and to embody its ideals in our own lives and actions.

When one reaches the end of the Lynching Memorial in Montgomery, having passed underneath the thousands of names suspended from the ceiling, one faces a wall with these words inscribed:

For the hanged and the beaten.

For the shot, drowned and burned.

For the tortured, tormented and terrorized.

For those abandoned by the rule of law.

We will remember.

With hope because hopelessness is the enemy of justice.

With courage because peace requires bravery.

With persistence because justice is a constant struggle.

With faith because we shall overcome.

Shabbat Shalom and love to all,

Rabbi Jonathan Kligler

PS This is an appropriate time to remind you all that you can find inspiration in the CD that I made with Kim and Reggie Harris, Let My People Go: A Jewish and African American Celebration of Freedom. It is available through the Woodstock Jewish Congregation, and also at Amazon.com.